Romanesque Period

The Romanesque Period

The Romanesque Period

By

Varo Borja

In this essay, I will attempt to describe briefly Feudalism in Western Europe, The Crusades and why they happened, and also the plan and brief description of a Pilgrimage church in Western Europe. This is quite a task, so I will begin immediately.

Professor Gerhard Rempel, of Western New England College, describes feudalism as having three basic attributes: “ fragmentation of political power, public power in private hands, and armed forces secured through private contracts”. Feudalism first came into being in Western Europe during the eighth century A.D., by granting estates to Knights (or the lowest caste of aristocracy, consisting basically of professional warriors) in return for military service. Feudalism differed throughout Europe, with the classic model in effect in Norman France. Feudalism in Germany differed slightly (mainly because it was more centralized; there was an emperor in Germany), and in Russia and the Near East it didn’t exist at all. The main reason for the development of a feudalist state was the influx of the Muslims from Spain and the Near East. Feudalism was created as a means (although a weak one) of defense against these Muslim (or Moorish) invaders. Being essentially decentralized in nature (in contrast with the centralization of the Roman Empire), the feudalist state was divided up into land holdings called “fiefs”. These parcels of land were distributed to the various aristocracy of the region (a process called “subinfeudation”) with the largest portions belonging to the sovereign Lord or King (or in the case of Germany, the Emperor.) The size of the estates were divided by size in descending order in this fashion: first, the Dukes, then the Counts, the Viscounts, the Barons, the Earls, the Margraves, and at the last the individual Knights. The Knights at the bottom of the ladder were relatively poor, and had few peasants (if any) to work their estates. At the very bottom of the ladder were the peasants, who were tied to their respective estates from birth, and had little or no chance of ever escaping a life of constant toil and ignorance.

The basic weaknesses of Feudalism were in the decentralized aspect of the system, which led to infighting between the various Lords (title given to the owner of an estate) and the bickering and chicanery (and general disrespect for authority) associated with obtaining and preserving these “titles”. To succeed in this system basically only two things were needed: a strong right arm and a clever mind. Several of the Duchies and Counties of the Medieval world were created through sheer butchery and backstabbing. In fact, the rapine, infighting, and general chaos were so great that a general code of conduct called “chivalry” was instituted and quickly became fashionable. Although much better in theory than in practice, chivalry was one of the basic proponents of what I will discuss next: The Crusades.

The Crusades were a series of holy wars that were undertaken against the Muslims (or Moors), with the purpose of reclaiming the holy city of Jerusalem. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the Crusades are listed thus:

It has been customary to describe the Crusades as eight in number:

- the first, 1095-1101;

- the second, headed by Louis VII, 1145-47;

- the third, conducted by Philip Augustus and Richard Coeur-de-Lion, 1188-92;

- the fourth, during which Constantinople was taken, 1204;

- the fifth, which included the conquest of Damietta, 1217;

- the sixth, in which Frederick II took part (1228-29); also Thibaud de Champagne and Richard of Cornwall (1239);

- the seventh, led by St. Louis, 1249-52;

- the eighth, also under St. Louis, 1270.

It would fill volumes if I expounded on the Crusades in detail, but I will give a brief account of why they happened. For centuries, Western Christians had made pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and in particular to the Holy Sepulcher (the Tomb of Christ) to pay homage to the holiness of the Lord. Most of the more notable princes had done this, including the Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne, as well as several of the popes from the time of Constantine up until the end of the first millennium. These Christians had enjoyed the protection, if not the blessing, of the Moorish peoples who inhabited Jerusalem and the surrounding area for centuries. However, with the rise of Hakem, a Fatimite Caliph (or Muslim cleric) of Egypt and his hatred for the infidels and purity of Muslim doctrine, the order was given for the expulsion of the infidels from Jerusalem and the destruction of the Holy Sepulcher. Although a definite turning point in the politics of the region, this event didn’t deter the Western Christians from making pilgrimages. In fact, a new religious fervor inaugurated in the eleventh century propelled many Christians, even of the lower classes to make the journey to Jerusalem. This new influx of pilgrims resulted in the general persecution of all Near Eastern Christians, and was one of the direct (or more advertised) reasons for the Crusades.

In reality, the Crusades were a chance (seen first by Pope Urban II) for the implementation of a Holy War (or grand cause) that would supposedly bring out the best in the unruly (at best) Lords of Christendom and end the infighting and slaughter inherent to the feudal system. It would also (supposedly) stop the influx of the Moors into Spain and the Byzantine Empire and act as a dam against the religion of the Muslims. The Crusades were a very complex series of Holy Wars undertaken with much zeal, but with sometimes very spurious motives. In fact, many of the “Crusaders” never even left their villages, and were content with the slaughter of the “infidels” at home, who were mostly of Jewish extraction. The majority of the clergy did not condone the general slaughter of the Jews during the 12th and 13th centuries however, and many persecuted Jews were hidden or given assistance by the various monasteries and local parishes throughout the west.

Perhaps the greatest accomplishment of the Romanesque period (which included most of the Crusades) was the establishment of the pilgrimage churches along the routes taken by the zealous, if ill conceived Crusaders. Many of these churches were built, but for the sake of brevity and to give the reader a general idea of the basic outline of these holy structures, I will describe only one.

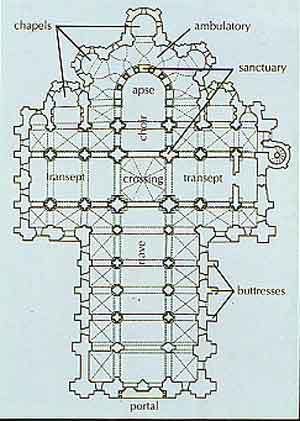

The Abbey church of Saint Foy was a masterpiece of the Romanesque period, and will serve as a shining example of the architecture of its time. Built by the work of the Conques monks, this beautiful structure was built before Saint Sernin of Toulouse, but had basically the same floor plan. Based on the general Basilica type from early Christian and Imperial times, Saint Foy contained a nave and a choir that was surrounded by an ambulatory. The choir was the place where the statue of Saint Foy (a small girl who had been martyred at the hands of the ministers of Diocletian; her bones were brought to the church in the ninth century and venerated with much religious zeal) and other holy relics were kept. The nave and the transept (or crossing) were built with much additional space so hundreds of pilgrims could hear the sermon and take the Eucharist (Lord’s Supper) from the priest at the high altar at the face of the choir. Saint Foy also contains a dome settled at the intersection of two perpendicular axes over the high altar (see http: //www.conques.com/visite31.htm for these notes). The Abbey church of Saint Foy was based on the cruciform plan, and had radiating chapels much like Saint Sernin. Saint Foy was designed with utility at the forefront, but it also contains one of the masterpieces of Romanesque sculpture: The Tympanum of the Last Judgment (which is much like that found at Autun, in Burgundy.)

This tympanum (the frieze over the doors, usually at the narthex) is found at the western portal of Saint Foy, and is sheltered under a deep semi-circular arch. It contains 124 figures, and is 6.7 meters wide and 3.6 meters high, and has been preserved to the present day in almost pristine condition. According to http://www.conques.com/, the overall composition is “Very simple: the huge semi-circle of the tympanum is composed of three superposed registers split by the strips which are reserved for engraved inscriptions. In order to fill in these registers, the author divided them in a series of compartments, which correspond to the twenty panels in yellow limestone he sculpted at ground level before assembling them like a gigantic jigsaw puzzle. This division, easy to discern, has been skillfully made given that one joint never intersects one figure or one scene.” The theme of the tympanum is, of course, the Last Judgment, and features Christ enthroned at the center surrounded by images of frightened and hapless supplicants who are either being protected by angels or harassed by demons. Christ’s right hand is raised toward heaven, signifying his acceptance of the supplicants on his right into the Kingdom of Heaven. His left hand however is lowered, damning those unfortunate souls on his left to an eternity of fire and torment. It is interesting to note that this theme was very prevalent during the Middle Ages, and must have been very sobering to all those who entered the Abbey Church of Saint Foy.

In conclusion, I have found this paper to be very informative, not only in an historical sense, but in a spiritual sense as well. My research has shown me how far Western society has come from the times of Holy Wars and the virtual enslavement of a whole race of people to such a failed concept as Feudalism. However, we have not come as far as some might think. The Iraq war has been categorized by some as a type of “Crusade” against the infidel Muslims and their terrorist factions. It’s a shame that people in this day and age of ultra modern enlightenment still believe that such chicanery and nonsense as a “war authorized by God” is a necessary thing, and that the people in charge of such acts of violence don’t have (much like pope Urban II) ulterior motives. Perhaps one day the human race will outgrow this very blatant “tribal” mentality, but obviously it hasn’t done so yet. Maybe like the Crusades of the 11th and 12th centuries, we will be graced with a few monuments to the better side of human nature, like those found at Saint Foy and Saint Sernin. Maybe one day mankind will be able to make such beautiful pieces of art as the Tympanum of the Last Judgment without the promptings of hatred or bigotry, and then we will be able to say that we have truly passed out of the Dark Ages.

No comments:

Post a Comment