The Burial of the Count of Orgasz

The Burial of the Count of Orgasz

The Burial of the Count of Orgasz

By

Varo Borja

This is where El Greco sets before us, in a highly compressed form the wisdom he has brought to his art, his knowledge, his expertise, his composite imagination and his expressive power. –Marina Lambaki-Plaka

This quote, from a noted Art Historian, sums up the power and majesty unfurled by El Greco (Doménicos Theotokópoulos) in his rendering of the Burial of the Count of Orgasz. In this essay I will relate to the reader a small amount of background on The Burial of the Count of Orgasz, attempt an analysis of this famous painting according to the iconography and allegory used, and also offer a summation of why, in my opinion, this painting has lasting value and an appeal that transcends the barriers of time and nationality.

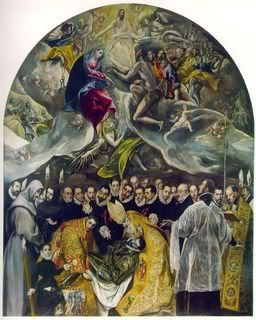

Considered by most to be his greatest painting, The Burial of the Count of Orgasz is the primary decoration for the funerary chapel of Gonzalo de Ruiz, Lord of Orgasz at the parish church at Santo Tome, in Toledo. Ruiz was a very pious man who reigned beneficently in the late 13th to early 14th centuries in Toledo. At the time of his death (1323 c.e.), he bequeathed an annual donation to the parish church where he was buried, to be collected from the citizens of Orgasz. According to legend, the Count was so pious and had done so many good works that saints Stephen and Augustine miraculously appeared at his burial and lowered his body into the tomb as a sign of holy favor. The parish church where this miracle occurred (Santo Tome), and which also received the generous donation from the citizenry of Orgasz, also happened to be the same church that the master known as El Greco attended mass on a regular basis with his son. According to El Greco of Toledo (Little, Brown and Company, Boston), “Around 1562, the people of Orgasz decided to stop making the annual donation, probably hoping that the memory of the bequest would slip into oblivion.” However, due to the shrewdness of the parish priest, the donation was resumed after an award from the chancellery in Valladolid in the parish’s favor in the matter. The renewed donation allowed for the chapel of the Count to be remodeled, and was substantial enough for a funerary painting to be undertaken. El Greco was named as the painter of the new work, and the result was to be his masterpiece, The Burial of the Count of Orgasz.

According to Wikipedia, El Greco obtained his commission for The Burial of the Count of Orgasz on March 12, 1586. He was given very simple instructions as to the composition of the work, with the primary focus given to the miracle of saints Stephen and Augustine lowering the body of the Count into his grave. It is worth quoting the source of El Greco’s instructions from the parish priest, Andre Nuñez de Madrid, for the painting here, as they are quite brief and illuminate the general composition of the piece:

“This is to be done on canvas down to the epitaph. Below the epitaph there is to be a fresco in which the sepulcher is painted. On the canvas, he is to paint the scene in which the parish priest and other clerics were saying the prayers, about to bury Don Gonzalo de Ruiz, Lord of Orgasz, when Saint Augustine and Saint Stephen descended to bury the body of this gentleman, one holding the head and the other the feet, and placing him in the sepulcher. Around the scene should be many people who are looking at it and, above all this, there is to be an open sky showing the glory of the heavens.” (El Greco of Toledo, pg. 125)

It went without saying that the piece was to have elements reinforcing Counter Reformation doctrine, two of which I will discuss shortly. According to El Greco of Toledo, a lengthy Latin inscription was composed by Dr. Alvar Gomez de Castro (a poet residing in Toledo) that read in part that the chapel was donated “Beneficis et Pietati” –to the beneficent and pious saints, the saints who performed good works. El Greco worked this epitaph into the painting as a means of furthering Counter Reformation theology, which insisted that salvation might be obtained by good works, as well as faith. The impetus for the miracle concerned with the Count was said to have been his lavish donations to the clergy and his beneficence to the poor during his lifetime, thereby confirming that good works were a means to salvation. The Protestants in England, Holland, and Germany, led primarily by the pen of such men as John Calvin, denied the acquisition of salvation by good works and insisted that salvation by grace through faith was the only means of escaping the fires of Hell.

Another important Counter Reformation idea is shown through the content of the work in both zones of the painting. This idea is the intercession of the saints and Mary for entrance into heaven. As is shown, the Count in the earthly realm is being lowered into his grave by saints Augustine and Stephen (Augustine on the right, young Stephen on the left) and in the heavenly realm, the naked and supplicant count is being welcomed in and interceded for by the heavenly saints and the Virgin Mary, who plays a predominant role in the painting. The Virgin is displayed in her typical, Byzantine iconographic garb of red and blue (El Greco hailed originally from Crete, a land under the influence of the Byzantine church) signifying perhaps the blood of Christ and her own tears for the faithful. Christ is displayed in the center of the heavenly realm of the painting in his traditional iconographic loincloth of white (signifying purity), but he is displayed more as an afterthought, or as a type of given in a theorem relying primarily on the emphasis given to the saints and the Virgin Mary. Saints Stephen and Augustine are portrayed in rich vestments of gold and silk, signifying their earthly authority as well as the glory given to them in heaven. The funeral of the count is rendered with a litany of what most scholars believe to be the likenesses of the most famous personages of Toledo at the time, also weeping and interceding for him from an earthly standpoint, therefore giving them accord with the idea of intercession after death by the living, another Counter Reformation tenet.

In conclusion, I feel that it is important to realize that although this painting was executed at a time of great hostility due to the schism of the Church, it retains much that is pertinent to us today. In the lower left hand corner of the painting, El Greco portrayed a likeness of his son Jorge Manuel, with, according to Belinda Coles, a small handkerchief in his pocket. To quote her: “If you were able to take a closer look at this painting, you would find on the handkerchief of the boy in the painting, the artist's own signature, as well as the date '1578' - the year of Jorge Manuel's birth. The boy points to the body of the deceased, thus bringing together birth and death.” The artist is trying to convey a message to us here, I feel, that future generations must continue to uphold that which is right and holy, and to not fear death and the grave. By giving his own son such close proximity with the deceased, it is almost as if he is saying that the human soul dies and is constantly reborn, much as Christ was after his crucifixion and as we can be, through good works as well as faith. Also, El Greco adorned the attendees of the funeral in contemporary dress, signifying the utterly up to date concern of the saints for the souls of the living and the dead, and God’s ever renewed interest in mankind and his attainment of salvation. His depiction of heaven in the work is timeless, reassuring us that underlying all is the assurance of the Blessed Realm, a place of rest and redemption for those that carry out the will of God and live to good purpose here on this temporal plane. El Greco was a man of vision. His work wasn’t truly appreciated until the time of the abstract expressionists such as Jackson Pollack and the cubist movement headed by Picasso. With such a far reaching legacy in the field of painting, and the powerful allegories that he presented, El Greco is truly one of the great masters of Westen Art, and The Count of Orgasz, as his masterpiece, one of the greatest paintings of all time.

Bibliography

El Greco of Toledo: Johnathon Brown, William B. Jordan, Richard L. Kagan, Alfonso E. Perez-Sanchez. Little Brown and Company, Boston. 1982.

Wikipedia: found at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Greco

Belinda Coles.htm: found at: http://www.edu.pe.ca/rural/class_webs/art/belinda_coles.htm